| |

| |

Ice bridge supporting Wilkins Ice Shelf collapses

8 April 2009, National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC)

An ice bridge connecting Latady Island and the Wilkins Ice Shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula to Charcot Island has disintegrated.

The event continues a series of breakups that began in March 2008 on the ice shelf, and highlights the effect that climate change is having on the region.

See Antarctic ice shelf disintegration See Antarctic ice shelf disintegration

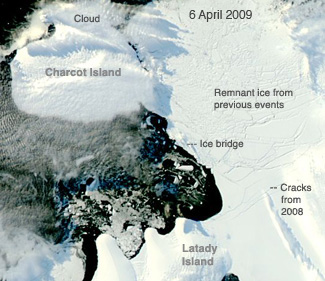

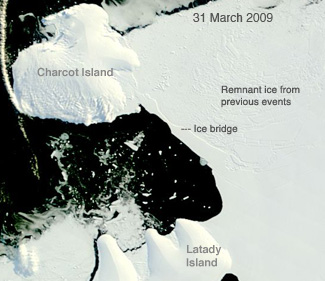

The shattering of the ice bridge between March 31, 2009 and April 6, 2009, which was bracing the remaining portions of the Wilkins Ice Shelf, will now allow a mass of broken ice and icebergs to drift into the Southern Ocean.

Scientists at NSIDC and around the world have been watching the ice bridge since last March, anticipating its collapse.

Now that it has broken up, researchers are closely monitoring the remaining portion of the Wilkins Ice Shelf to see if the loss of the ice bridge allows the ice shelf to collapse further.

The Wilkins is following a pattern of instability and rapid collapse that many Antarctic Peninsula ice shelves have experienced in recent years. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

The western Antarctic Peninsula has had the biggest temperature increase on Earth in the last 50 years, rising 0.5°C (0.9 °F) each decade. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

Scientists think that the dramatic loss of these ice shelves, which have existed for hundreds to thousands of years, is an important sign of climate change in the Southern Hemisphere.

The loss of an ice shelf can also allow the glaciers that feed into it to start flowing ice into the ocean at an accelerated rate, contributing to a rise in global sea levels.

The Wilkins Ice Shelf first began to break up in the mid-1990s. Last March, it lost another 400 sq.km (160 sq.miles) in a rapid retreat, and continued to form new cracks over the winter. The Wilkins Ice Shelf is located on the southwestern Antarctic Peninsula, the fastest-warming region on Earth. In the past 50 years, the Peninsula has warmed 2.5°C (4°F).

In the early 1990s, the Wilkins Ice Shelf had a total area of 17,400 sq.km (6,700 sq.miles). Events in 1998 and the early years of this decade reduced that to roughly 13,680 sq.km (5,280 sq.miles).

In 2008 there were a series of rapid repeated calvings which produced ice shelf pieces small enough to topple over.

Rifting of large sections of the shelf, leading to large tabular iceberg calvings, shrunk the area of stable shelf to roughly 10,300 sq.km (4,000 sq.miles). This amounted to a net loss within a year of approximately 3,600 sq.km (1,400 sq.miles). |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

Above: In the first image on March 31, 2009, the ice bridge was still intact with a smooth, unbroken surface. In the second image from less than a week later on April 6, the smooth bridge is replaced by chunks of ice.

The pieces of the former ice bridge join other chunks of ice that formed when the northern portion of the ice shelf broke apart throughout the previous decade. The broken pieces of the shelf have remained frozen in place since 1998.

Images: National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

The Wilkins ice bridge on 6th April 2009 (above top), and on 31 March (above).

Images: National Snow and Ice Data Center |

|

| |

|

| |

Cracks that formed in the ice shelf in late 2008, below and to the right of the bridge, expanded after the ice bridge broke and the remnant ice nearest the shelf shifted away, says Ted Scambos of NSIDC.

These changes are emphasized by differences in light between the two images. The Sun was low on April 6th, so clouds cast long shadows on the ice, highlighting cracks in the ice. On 31st March the Sun was relatively high, and the light more direct, casting less shadow outline. The cracks were first evident on 26th November 2008.

Many factors contributed to the collapse of the northern portion of the ice shelf, including brine on the ice, physical stresses on the shelf, and warming temperatures, says Scambos. During 2008, parts of the ice shelf to the left of the bridge broke away.

The ice bridge had been the last intact portion of the northern edge of the ice shelf. The southern portion of the Wilkins Ice Shelf which appears in the lower right corner of the images, is still intact, but may now be more vulnerable.

The collapse of the ice shelf will not contribute to a rise in sea level, because the ice had already been floating on ocean water. When other ice shelves such as the Larsen have collapsed, they allowed glaciers to pump more ice into the ocean at a faster rate, which did contribute to sea level rise.

The Wilkins Ice Shelf does not buttress any major glacier. It is the tenth major ice shelf to recently collapse, another sign that warming temperatures are impacting Earth’s fragile cryosphere. |

|

| |

|

| |

|